Nineteen Septillion Addresses - Setting up an ASN, obtaining IP addresses, and finding my way around the internet

Here’s the story of AS202858.

Recently I got curious as to where exactly IP addresses came from, and how does ’the internet’ know where packets addressed to one should actually end up. This article is a quick overview of what I discovered and how I got my hands on my own slice of the IPv6 address space, and how I used it practically. It’s a high-level overview, although with some detail on particular configs that took me a little while to figure out in case it might help someone doing something similar.

I’ve been fortunate that I use two ISPs here in Finland that support IPv6 and it ‘just works’ (admittedly having to pay extra to one of them for it). The consumer-grade routers hand out publicly routable addresses to devices, and I can access them from anywhere else in the world with an IPv6 connection without resorting to portforwarding or VPN trickery. Sure, the addresses my change, but I’m not going to be remembering a 128-bit IP address, so setting up a simple DDNS script to run on each device (Raspberry Pis of various flavours) works a charm - and also allows me to get a TLS certificate for each one from LetsEncrypt.

For a while though, we were going to be traveling, and for cheapness purposes (the irony of which will become apparent further on in this article) - we were going to be relying on a pre-paid 4G connection. It was fast enough for our needs, but had no IPv6 service, and was CGNAT-ed, thus putting me beyond reach of my home-lab while away.

Of course, it’s easy and cheap enough to just bounce off of a dual-stack VPS somewhere, but I had gotten thinking, “who owns an IP address anyway? If there are so many IPv6 ones now available, why can’t I have my very own one to keep? Why do I have to use the one my ISP gives me?”…

Prefixes

In a perfect/simpler world, networks, that are in turn networked to each other, forming the internet, would use an addressing scheme similar to phone extension numbers. The network itself would have a ‘prefix’, say, 24 bits long, and a device or interface connected that network would have its own 8 bit number assigned to it and appended to that prefix.

This is of course how IPv4 addresses were (sort of) issued, with prefixes of varying lengths between 8 and 24 bits (after the introduction of CIDR, in 1990’s - and I’m overly simplifying these details here).

For practical reasons, a 24 bit length prefix is the smallest allocation that is now made on the public internet. When we say smallest here, we mean in terms of maximum number of hosts that the prefix will support. The fewer bits that are used by the prefix, the more bits there are left to assign to each host, hence a /8 - or a prefix consisting of 8 bits, will support a larger number of individual hosts than the /24. Incidentally, /n is how the size of the prefix is expressed in bits in an address, i.e. 192.168.0.1/24 means the first 24 bits of the address form the prefix of this address

IPv6 follows a similar scheme, although out of the 128 bit address, the last 64 are always (almost always, there are some special purpose exceptions) used as a unique interface identifier, with the first 64 bits then being split between a network prefix and a subnet ID. Furthermore, for globally routable addresses, currently, the first (highest) 64 bits of the address must start 001 - or written in the more common notation: 2000::/3. Similar to IPv4, there are some reserved ranges (e.g. 10.0.0.0/8 is for use in a private network, so wouldn’t be routable across the internet), but dis-similarly, there is a reserved range explicitly for public internet.

Again, for practical reasons, the smallest allocation (largest number of bits used for a prefix) that is routed across the public internet for IPv6 is a /48.

It is these ‘prefixes’ that are registered to owners.

Getting a prefix

Let’s first see what it would take to be given my own chunk (/24) of IPv4 addresses to use however I wanted, registered to me.

It’s well known that these are a scarce resource nowadays, my original problem here stemming from the fact that companies won’t even give a single one out to a paying subscriber - falling back to CGNAT.

The first port of call would be the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority - I want a number on the internet after all. Here we learn that responsibility for assigning addresses is delegated to regional organisations, called Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). As I am in Europe, the Réseaux IP Européens (RIPE) is the one I want (not that there’s much practically preventing someone from dealing with one outside of ’their’ region).

We learn quite quickly from the page that IPv4 has run out, but you can join a waiting list - at the time of writing, getting close to two years long. The list is also only open to these things called ‘LIRs’.

Another option would be to see if someone is sitting on some IPv4 space that they’re not using, and would be so kind as to transfer it to me. Indeed there seem to be a healthy number of those, and they will readily do so, for a fee. (About $25-30 per address, so $7,000 for a /24).

With IPv6 prefixes, things are looking more hopeful. The page makes a lot of mention to becoming a RIPE member though in order to get one, or asking for a sponsoring LIR to help you out.

LIRs

It seems then that to receive any service from RIPE, you effectively have to either be, or use, an LIR - or Local Internet Registry.

Becoming an LIR means becoming a member of RIPE. The membership fee for this is approximately 1,800 EUR/year. Modest enough for a commercial organisation, but a bit out of my budget for hobbyist purposes.

Or you can find someone who is already an LIR to ‘sponsor’ any resources you might want such as IP addresses and Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs) - effectively your network’s own ID. This is reasonably inexpensive.

However, to actually set up a network, and receive an ASN and IP allocation, either as or through an LIR, RIPE require you to have agreements in place with two other providers to carry the traffic from your network. After all, the point is to create an inter-network, they’re not interested in assigning addresses to something that cannot be reached. This is where I discovered some complexity. Buying this service is not like buying a VPS. You are looking for someone who will effectively let you configure their routers to carry traffic for your IP addresses, and they need to be able to in turn tell their suppliers to configure their routers to know about your network and IP addresses (and so on and so on). With limited exceptions, a home ISP is also going to be uninterested in helping you out here (sadly I’m a little bit outside of AAISPs service area).

Effectively, you are looking for something called a BGP session. BGP, or Border Gateway Protocol is, among other things, the method by which routers can be configured automatically to route traffic to your IP addresses (or prefixes). If someone accepts your announcements of your IP address ranges over BGP, then they will route traffic that arrives in their network for your IP ranges to you. They will probably also then accept traffic from your network on to the rest of the internet - i.e they will supply you with Transit of your packets. In general, the people buying transit services are doing so for large scale networks, and will be transferring large amounts of traffic, so these again are usually priced accordingly and often require either some kind of physical servers present in a datacentre, or actually digging up a road to lay fibre to your premises. Note that there are a couple of hosting providers that will supply this with a VPS, such as Mythic Beasts in the UK and Vultr (worldwide). In the end however, I went with a company called Servperso (affiliate link), who supply a turn-key solution for setting up an ASN with RIPE, along with the necessary transit through both their and a partner’s network.

Setup

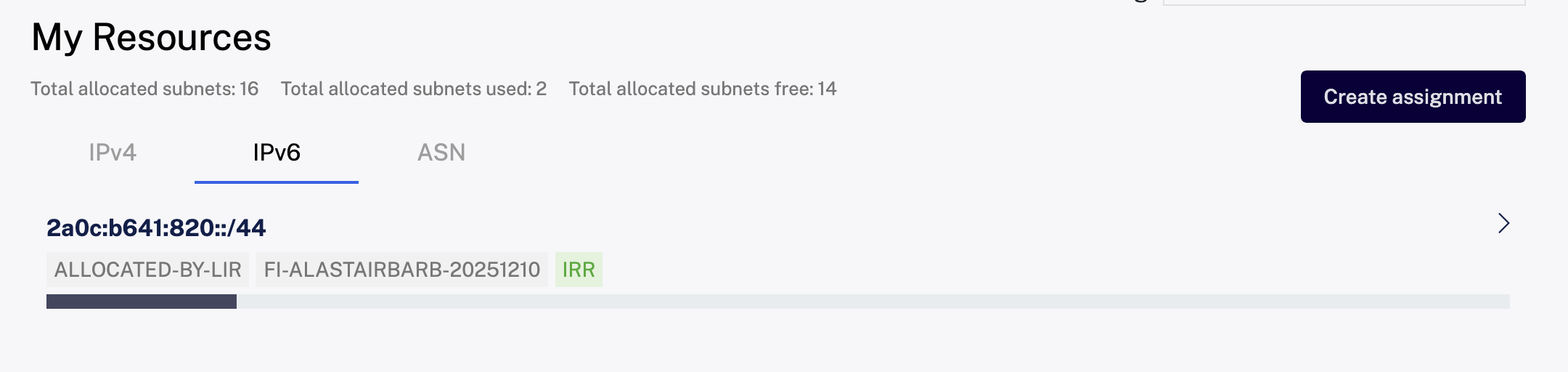

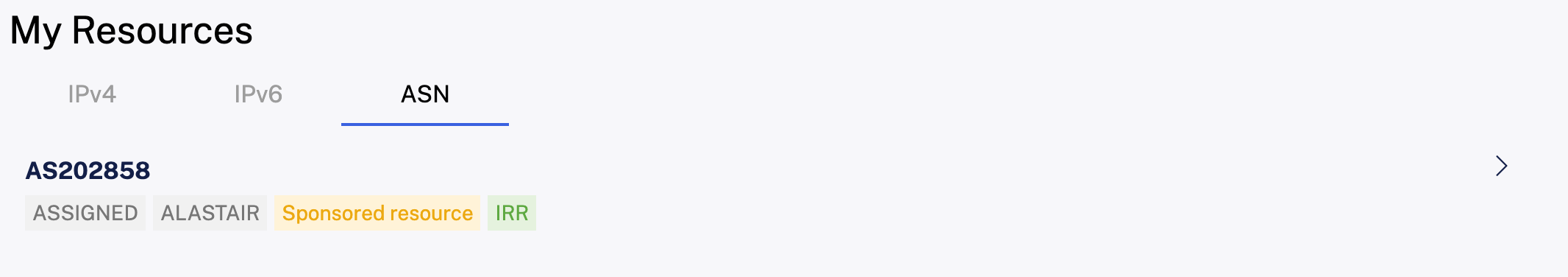

After handling some documentation, I was soon the proud owner of AS202858, and a /44 of IPv6 space. (‘Provider Aggregate’ (PA) space. I’m going to gloss over the details of this and Provider Independent space here)

This link above is to a website called bgp.tools. I’d heard of it before but wasn’t really sure I understood what it does. Now I do (or at least, a bit more of it) and it’s quite amazing. You can use it to explore the entire internet ecosystem; determining which networks connect to others, who administers IP addresses, and importantly, in real time, see BGP announcements as they are made from ASNs - so extremely useful to see if your config is getting out as intended.

BIRD

Connectivity to Servperso was supplied in the form of a VPS with two Ethernet interfaces assigned. Both have different public IPv6 addresses (outside of my allocation) and one an IPv4 address too. After setup, SSHing in was like any other normal VPS. Each interface existed within two separate networks (the two different Autonomous Systems for transit) - and so could both reach to the internet. I was also given the IP addresses of the router to make BGP announcements to.

I had a /44 of IPv6 space allocated to me in the RIPE DB. From this I created two smaller assignments of /48 each (the rest is still there, just not routed to anything at this time). I now wanted to announce these to the routers at Servperso, telling them to forward any traffic for either of these prefixes to this VPS. To do this, we need something that speaks BGP for us, and a popular choice of software for this is called BIRD. Curiously though, the way in which it appears to have been set up in my case is that the router connects to to deamon running on this VPS on port 179, connections to 179 on the router where immediately closed, although this would make sense from a security perspective.

Here is how the interfaces look on the system, and the BIRD configuration I used. Actual IP addresses of the host and routers have been obfuscated. Loopback and link-local interfaces/addresses aren’t shown because they’re not very interesting.

Network Interfaces

$ ip a

1: ens18: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc fq_codel state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 45.154.1.23/27 brd 45.154.1.1 scope global ens18

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 2a0c:b640::12:3/112 scope global

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: ens19: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc fq_codel state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 11:11:11:11:11:11 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.10.10.10/24 scope global ens19

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 2a0c:b641::45:6/64 scope global

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

Servperso BIRD Configuration

router id 45.154.1.23;

debug protocols all;

protocol static {

ipv6;

route 2a0c:b641:820::/48 unreachable;

}

protocol static {

ipv6;

route 2a0c:b641:821::/48 unreachable;

}

# Prefix filter to avoid BGP leaks

filter filter_to_upstream {

if (net.type = NET_IP6 && net ~ [ 2a0c:b641:820::/48, 2a0c:b641:821::/48 ]) then accept;

reject;

};

protocol bgp BGP_Servperso_V6 {

keepalive time 20;

hold time 60;

local as 202858;

neighbor 2a0c:b640::ffff as 34872;

source address 2a0c:b640::12:3;

ipv6 {

import none;

export filter filter_to_upstream;

};

multihop;

}

protocol bgp BGP_Servperso_V6_Dual {

keepalive time 20;

hold time 60;

local as 202858;

neighbor 2a0c:b641::ffff as 210233;

source address 2a0c:b641::45:6;

ipv6 {

import none;

export filter filter_to_upstream;

};

multihop;

}

The main parts here are:

- protocol static blocks define the static routes that we have, to our two IPv6 prefixes. Counter-intuitively, we mark them as ‘unreachable’ here. This is because in this configuration - we want packets to be returned as unreachable by default, unless there is something else configured to route them (which we shall set up next) on the system. Adding them here though makes BIRD aware of them.

- filter This is important as it explicitly marks the networks we wish to allow to our upstream. It’s a line of defence should we add in another completely related internal route. Most well-behaved upstreams will also do filtering of their own (perhaps checking against a database that the owner of the prefix is someone they expect to be talking to them) - but it’s good practice to keep this sort of thing under control. In the past, screw ups in BGP have broken the internet in the literal non-meme based meaning of that phrase.

- protocol bgp blocks actually tell BIRD to talk BGP to the peers. The configuration here is rather specific to the setup I found at Servperso, but the important bits are my own AS number, the peer’s number and IP address, and the instructions for import and export:

- import What to bring in from the external peer and add to our system’s route table. Here I don’t want to bring in anything as it would be the entire internet’s routing table and I don’t have a need to use that, as by default I will just send all my traffic out over one of the interfaces.

- export The main bit here, run all of the routes defined elsewhere (in this case, just those above static ones) through the mentioned filter, and send them on to this peer.

If all is well, we should be able to use the birdc command to see something like the following:

$ birdc show protocols

BIRD 2.17.1 ready.

Name Proto Table State Since Info

static1 Static master6 up 2025-12-22

static2 Static master6 up 2025-12-22

BGP_Servperso_V6 BGP --- up 2025-12-22 Established

BGP_Servperso_V6_Dual BGP --- up 2026-01-01 Established

For fun, we can create a dummy interface, attach one of our IP addresses to it, then have a script listen there and send it a message:

$ ip link add name test type dummy

$ ip ip addr add 2a0c:b641:820::1/64 dev test

$ ip a

21: test: <BROADCAST,NOARP> mtu 1500 qdisc noop state DOWN group default qlen 1000

link/ether 6a:de:3a:ef:1b:53 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet6 2a0c:b641:820::1/64 scope global

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

$ nc -l 2a0c:b641:820::1 1234

$ nc 2a0c:b641:820::1 1234

Hello, world!

And you should see the message on the first one!

You should certainly enable a firewall such as UFW on any VPSs handling traffic

Tunneling out

Whilst it’s great that we can now route uncountable numbers of IP addresses to a single VPS, it’s probably a nice idea if we can use these addresses for something else. For example, I’d like my devices behind the double-NAT IPv4 only connection to be able to join in the fun. In this case, the only really sensible way would be to use some kind of tunneling technology.

After doing some research, I decided to purchase the above Teltonika router (I was in the UK at the time, I can recommend Solwise as a supplier). These are capable boxes of tricks (based on OpenWRT) and are manufactured in Europe too.

Initially I wanted to use P2TP (no IPSEC). Encryption isn’t really a concern, I am not setting up a private network here - everything going in one interface is going to be decrypted and sent straight back out of the other (but I do want to ensure I am the only person sending traffic to it). Unfortunately, I struggled to get this set up with IPv6. GRE would have been ideal, but that would have needed a fixed public IP address at the router end, exactly what I didn’t have.

I was originally unfamiliar with WireGuard - but that seems to absolutely be the way forward here. It’s incredibly lightweight and secure, and was supported natively by the router.

Wireguard VPS Config

This was simply a case of installing WireGuard on the server and creating an interface. I added the following postup/postdown configuration to the interface config:

PreUp = echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv6/conf/all/forwarding

PostUp = ip6tables -A FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT

PostUp = ip6tables -A FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT

PostDown = ip6tables -D FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT

PostDown = ip6tables -D FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT

(It is this setup, performed by the wq-quick command that adds the route to the prefix to the routing table, mentioned in the discussion about the ‘unreachable’ keyword in the BIRD config)

Along with assigning the interface an address from the prefix that I’m trying to route (2a0c:b641:821::/48), it’s also important to add the prefix to the AllowedIPs in the Peer block:

AllowedIPs = 2a0c:b641:821::/48

Configuring the Teltonika Router to Announce the IPv6 Prefix from WireGuard

This is where things get a bit more interesting as we’re going off-piste slightly here. Normally with SLAAC, a router gets an IPV6 prefix from the WAN side and advertises this to devices as they connect to the router, and they use this to form their addresses. With this process, there is nothing on the WAN side assigning the router a prefix, we need to tell it what to do.

This took me a good afternoon/day to figure out, so I’m sharing it here in detail in case anyone has a similar router and finds themselves trying to do something like this. Skip to the end if you’re not interested.

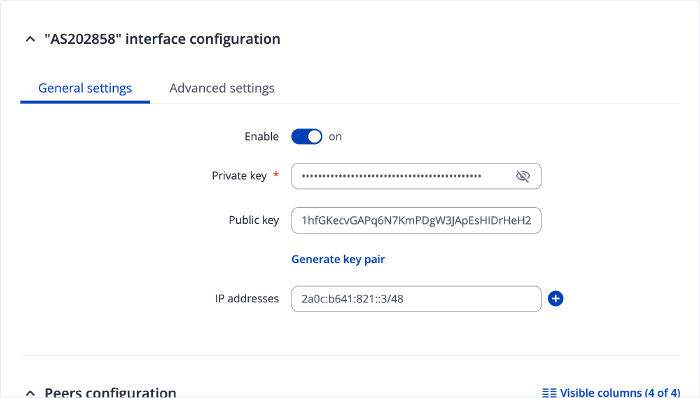

The WireGuard config is fairly vanilla. I gave this interface an IP address within the prefix - I’m unsure if it’s strictly necessary:

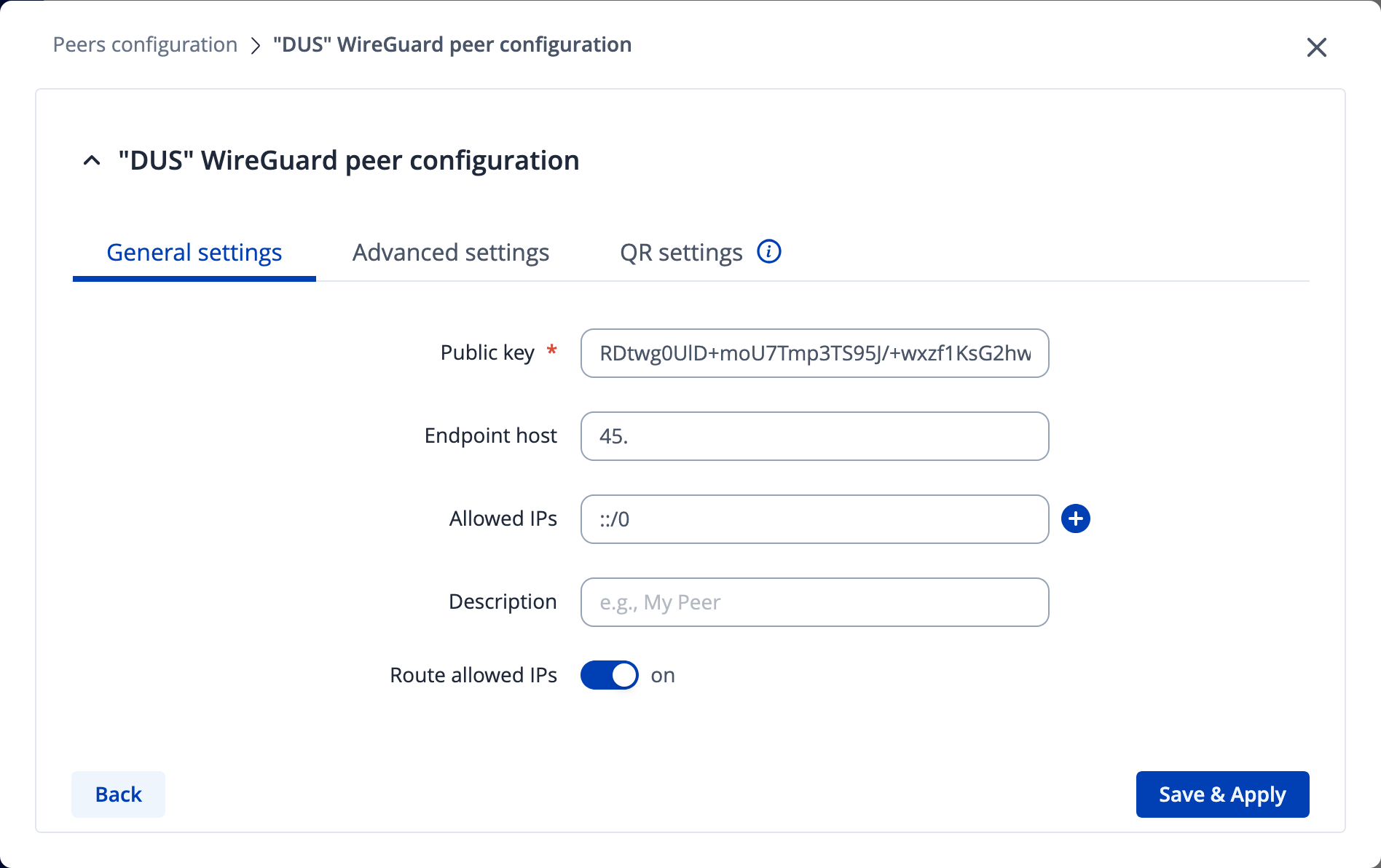

The peer section is particularly important - the allowed IPs must be ::/0 to route all IPv6 traffic to this peer, and naturally it follows that “Route allowed IPs” is set to ‘On’ :

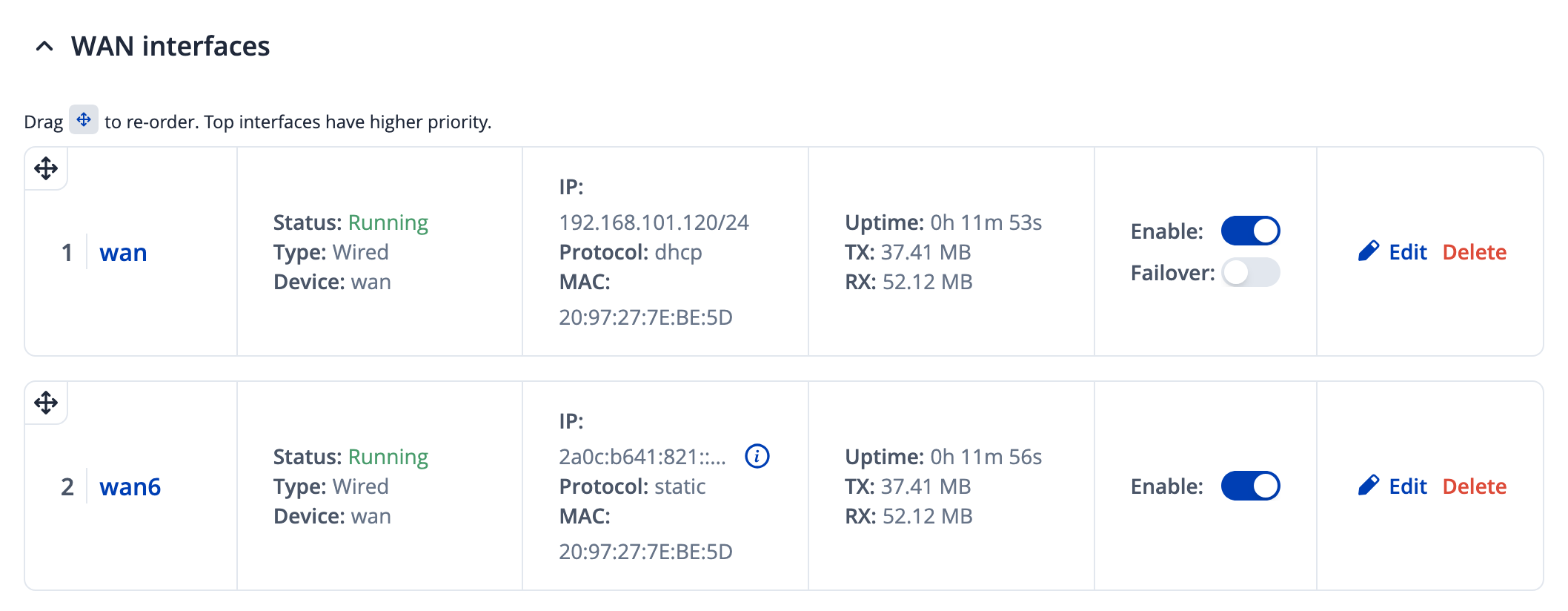

Next we need to do the interesting bit - which is tell the router to ’trust us and use the prefix we tell it to’. In the WAN settings, we’re looking to change the default wan6 object:

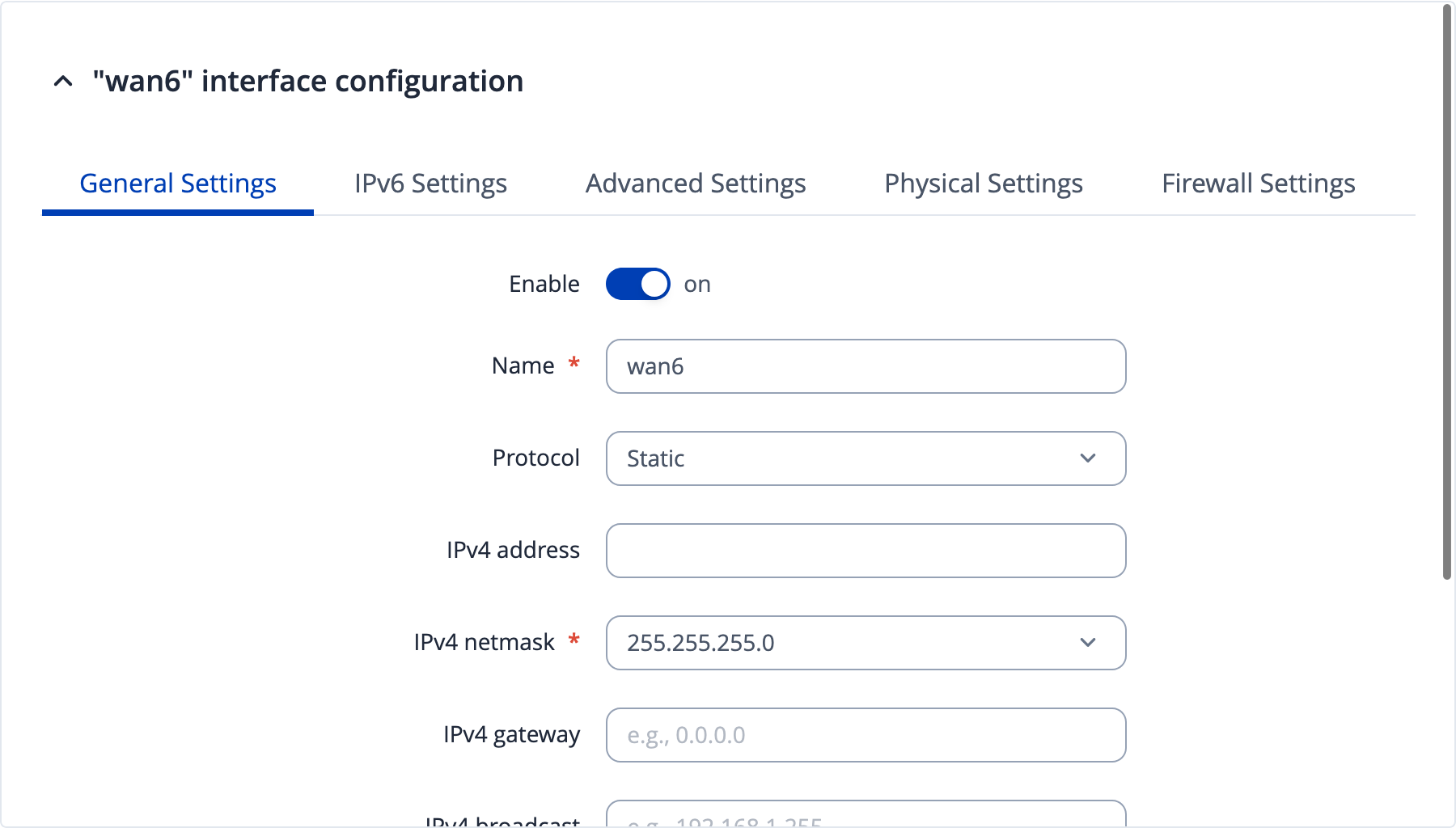

Change the protocol to ‘Static’. An IPv4 netmask seems mandatory here, but setting it to match that of the IPv4 wan interface seems to work fine.

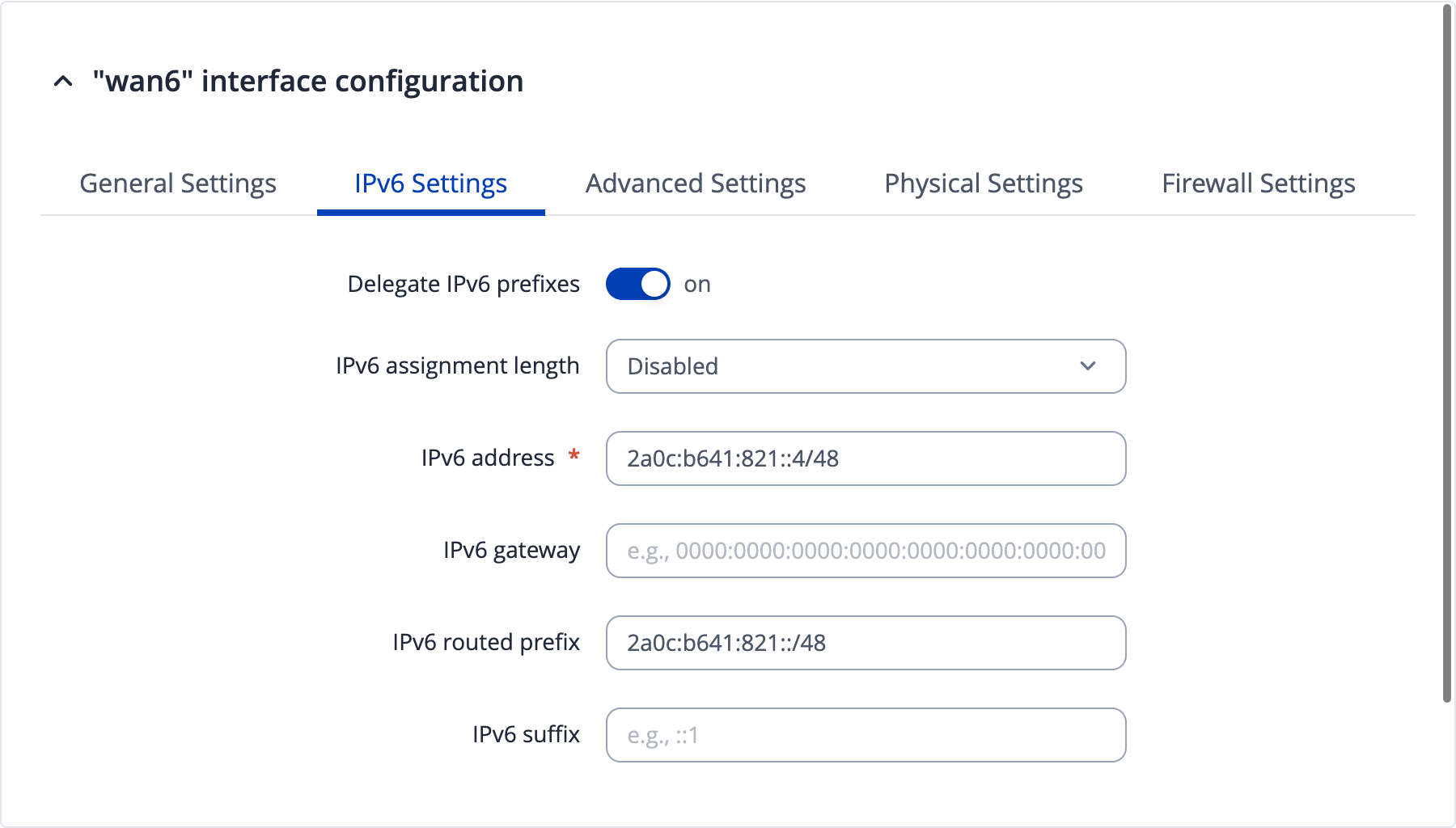

Under IPv6 settings, tell the router about our prefix. The IPv6 assignment length option should be disabled. Then I assigned yet another address to the router from the prefix, before explicitly specifying which prefix to assign to clients:

This now seems to work and assign addresses from our own routed prefix to devices in the network!

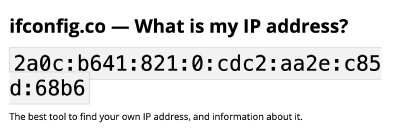

Shown above is the response from ifconfig.co for my web browser on my mac when now connected to the router’s WiFi.

This is one way to do this and I’m certain there are other more elegant solutions. I’d quite like to see if I could get the router to announce the prefixes itself using BGP and a private ASN to my public one for example (still over a tunnel).

Conclusion and Next Steps

Shown here is an extremely over-the-top, somewhat expensive, and with slightly lackluster performance, way of getting IPv6 (only) addresses when all you have is some kind of CGNAT connection. The biggest stumbling block for me right now is performance, the ‘router vps’ being located in Germany, whereas most of the things I wish to network are in Finland and the UK (although Germany is conveniently half-way-ish between I suppose).

Peering

But all is not lost! The network could be expanded with peering to other networks across Europe - and then we could also begin to create custom traffic policies to route the steps to take. There are some interesting projects such as locix and freetransit that aim to make connectivity for hobbyist networks as inexpensive as possible.

44Net - Back to IPv4

A very interesting piece of internet history is 44Net. Back in the ’80s, an entire /8 of IPv4 addresses were reserved for the use of the amateur radio community. That still exists today (some of it was sold a little while back, the funds used to manage the operations and also fund a variety of amateur radio projects worldwide - nice!), and I have requested a slice of a /24 to add to my network. I’m still waiting to hear back, but in the meantime it got me thinking, what if a part of the link between me and my router VPS in Germany could be RF? No extra hops!

Lots of fun stuff to try, let’s see what happens next!

References

Some useful links and resources I used whilst working on this: